I was not a hundred percent child when I was born. I was pulled out off my mother womb when I was just seven months old. I played and fought and recovered my own sickness until I turned nine. Or it could be, my parents fought hopeful and hopeless fights to save my life for consecutive nine years. My unidentified sickness was cured. Finally, I became a girl, girl that can competently work like other girls in the neighborhood. The childhood I remember was a competition between girl children who could work the most efficiently. Helping with household chores would be foremost trait a girl child should perfect. The more you work, more you become a treasure to your family. I gave my best to meet that status driven by ego, persuasion and fear. I worked and worked like a horse to not let my parents down in front of their society.

My parents, specially my mom, became the happiest mother in the community after being showered by compliments about her hard working child. I, too, felt proud of myself for making my parents proud. A tiny little girl, not even four feet tall, taking care of the entire household chores would amuse the entire community. I felt I was loved. A love that would be measured by the amount of work I do. I had no other option than to keep working and keep making people smile till the entire community knew of me.

I was barely eleven when we were taken to Dakshinkali temple for a family picnic with another family who just won a lawsuit of their land. We were a part of that picnic because my father was the lawyer who fought their case. Picnics were a rare occasion for me. Other boys and girls playing around, eating and drinking without having to do anything was not a general occurrence. I met new faces. I ate new food. I made new friends. But I never knew that I was going to meet my new family until I was told that the women who asked me to get a fire to light her cigarette was going to be my mother-in-law. That woman who smoked was interested in my famed working habits. She contemplated me becoming their daughter-in-law so that I can relieve her work loads. The marriage proposal had reached our house just a few days before the picnic.

My father was not to happy about it, “I’m not giving my girl to a family from Bhaktapur.” he said. I never asked about the grudge that he had of Bhaktapurians. Similarly, my to-be father-in-law also had similar sort of bitterness about people from Bhimsensthan, Kathmandu. I never asked about that either. Despite the denial from fathers from both the family, the marriage was fixed. My mother loved the groom-to-be and his mother loved the bride-to-be. Both the mothers confirmed our marriage. The boy was a seventh grader and was nineteen. He had four other options to choose from which he could marry. He chose me. When he was asked why he chose me, he said, “At least she is studying, she will continue to become an educated person.”

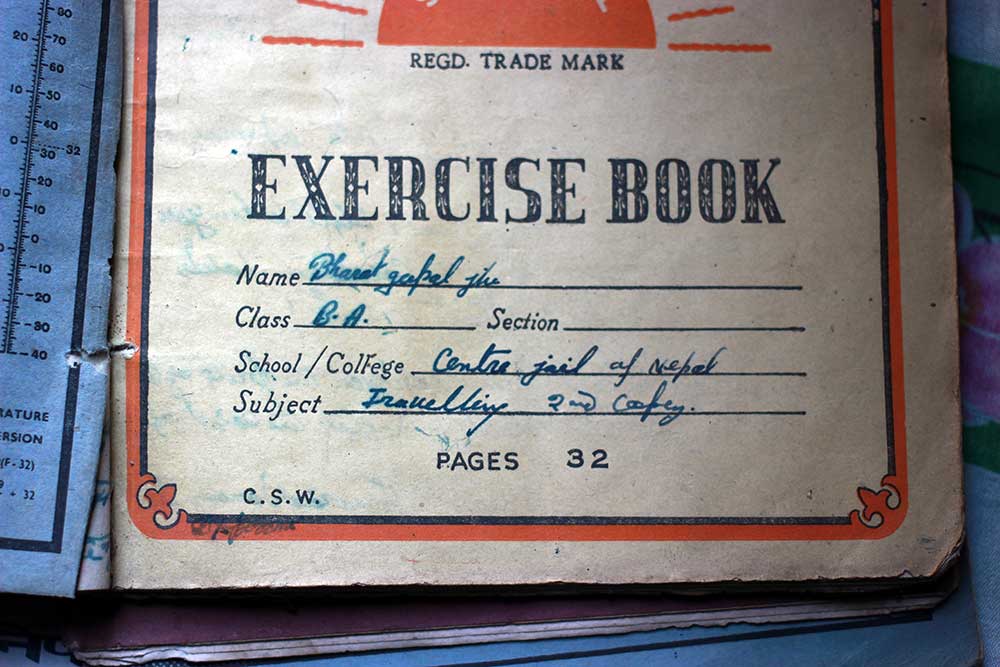

We got married. But our marriage came with a clause put forward by my father. Both the families assured him that I would not be going to my groom’s house until I finish my school leaving examination. I counted. I had seven more years to complete my school before shifting to another house in Bhaktapur. Marriage for me was nothing but my friend’s teasing me if they ever saw me talking to Bharat Gopal Jha, this boy I was told was my husband. It was nothing but an agreement between two families which, interestingly, assured my education. I was happy for that, if not for my marriage.

Time flew.

Bharat passed out his school and joined the Mahendra Ratna College in Tahachal which was few minutes away from our house in Bhimsensthan. He would often come to see me when he came to college. By then, I had already stopped going to school. I had to look after all the household work because my mother started getting sick. Seeing me not going to school, Bharat asked his mother to call me home and send me back to school. A slight hope of going back to the school emerged. But she harshly refused, said, “Do you want your mother to labor and let your wife go to the school?” That possibility too vanished. My love towards education got crushed, almost forever.

Since I was not studying anymore, there was no point for my in-laws to wait till I finished school. So I was taken to my husband’s house, deep in the chaotic alleyway of Ittachhen, Bhaktapur. A house comparatively messier than my parents house. I worked not only like a daughter but I had to work as a daughter-in-law. I dealt with it. For me, it was just as similar as working in my house just a bit more.

One day I came to know that my husband had not actually passed his SLC yet but had been coming to the college for political motives. It was the early years of democracy where people could carry out political activities openly. Bharat Gopal was a member of student wing affiliated to Nepali Congress and had been actively involved in politicizing the masses. It was during the election days of 1958, people started noticing Bharat speaking in various political gatherings. He was spotted along with various Nepali Congress leaders including BP Koirala and Ganeshman Singh. This news reached to my father as well. Filled with anger and anxiety, he shouted at my mom, “Have I not warned you before to not give my child to the family in Bhaktapur?” This time his concern was more to do with my future. But it was already too late. Bharat had already become a well-known figure in society, challenging the powerful status quo. My family thought it would bring bad omen to us.

Bharat was still a stranger to me although being my husband. He was more a political activist. He had more devotion towards society than to his family. In fact, it was still difficult for me to define what it actually meant to be a wife.

In the meantime, the elections took place on February 1959, resulting in a victory for the Nepali Congress. But in a short span of time, King Mahendra suspended the constitution, dissolved the elected parliament, dismissed the cabinet, imposed direct rule and imprisoned the then prime minister BP Koirala and his closest government colleagues. To defy the infamous 1960 Coup d’état, Bharat Gopal Jha along with other leaders started a protest against the King. He was arrested.

Everybody requested him to apologize in front of the King. He refused. He chose imprisonment to the freedom he would get after surrendering. His jail terms kept extending.

Although my husband was in prison, I would have nothing as such to talk or share with him. In fact, I was not sad when he was behind bars. I should have had that as a wife, but I didn’t. There were numerous unspoken conversations. Even the prison officers would laugh at our silent visits. After many visits, he showed some concern about me not going to school. But I was too busy working in the house and didn’t have time to get educated.

In the meantime, my father married another woman. When I went to visit my husband in prison after my father took a second wife I made him promise to re-admit me in school. He promised and spoke to his family. Next morning, I became a student again.

That must have been the first and last wish I asked of him. After three years of imprisonment, he was mysteriously killed.

I was just fourteen years old. While I was struggling to discover the meaning of being a wife, I became a widow.

I waited for the yearlong mourning and death ceremonies. After it was over, I resumed my study. I completed my school leaving examination and joined college. Since, I had to look after both the families, focusing completely on my studies became tougher. I failed Economics and English in college. Eventually, I stopped going to college and started teaching for a living. For almost twenty-three years I taught in various schools in Kathmandu. Simultaneously, I also played a political role of a wife of a martyr, representing my husband.

It was tough for me to become a widow when I could have lived a free teenage life. I never chose to become a bride. I never chose to remain a widow either. I never chose to be humiliated again and again being a single woman. But this society is brutal.

I neither became a wife nor a mother of a child but a widow of a martyr.

story & photos contributor: Bikkil Sthapit