While remembering my childhood, the memory that is stuck in my head is when I heard a unique, sweet rhythmic beat coming from the narrow streets. I heard it while going to school every day. Every time I hear those strange rhythmic sounds my heart would start dancing.

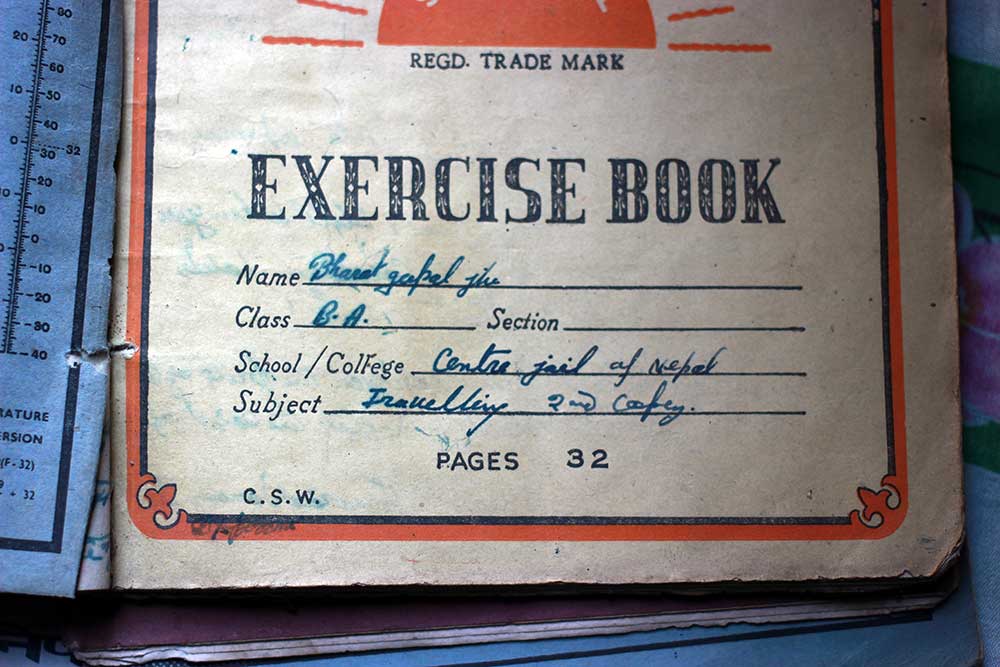

My ancestral house is in Jiri but my family moved to Sindhupalchowk for business. That’s where I grew up. I was sent to a government school while my brother went to a private school. I would have to walk for an hour while my brother got picked up by a bus every day. I never questioned that impartiality that was done to me rather I was thankful that I was given an opportunity to go to the school unlike other girls from the village. Life, in general, was difficult in the village. At a certain point in my childhood, we moved to Kathmandu for better livelihood possibilities.

I never questioned that impartiality that was done to me rather I was thankful that I was given an opportunity to go to the school

One day I saw a group of boys playing something which produced the same sound I would hear while going to school every day. That was the first time I saw the drums.

Girls playing musical instruments were rare. In fact, it would be considered bad-omen if women, in particular, do so. Even though there were barely any girls playing musical instruments, I didn’t let that stop me. When all the young teenage boys were forming music bands, I formed a band with the girls I played basketball with. I had no idea about music. But I knew that I wanted to become play the drum, become a drummer. After my 10th grade exams, I started taking drumming lessons. Financially it was very difficult for my mother; she still managed to save some money for my drum classes. Even though I didn’t own a drum at home, I was so passionate about it that I would put pillows in front of me as though they were drums and practice.

Girls playing musical instruments were rare. In fact, it would be considered bad-omen if women, in particular, do so. Even though there were barely any girls playing musical instruments, I didn’t let that stop me. When all the young teenage boys were forming music bands, I formed a band with the girls I played basketball with. I had no idea about music. But I knew that I wanted to become play the drum, become a drummer. After my 10th grade exams, I started taking drumming lessons. Financially it was very difficult for my mother; she still managed to save some money for my drum classes. Even though I didn’t own a drum at home, I was so passionate about it that I would put pillows in front of me as though they were drums and practice.

In the beginning, we went to learn music to show that girls can also play as boys but later on we became serious about music. After forming our band we were invited to perform at school. They asked the name of our band which we had never thought of it. One of our members, Sushma Ghalan, promptly suggested “Gorkhali Girls Band”. From that day the journey of our band started.

We started performing regularly in musical events. In many places, they would have their instruments for us to play but sometimes we were asked to bring our own instruments and we didn’t have any. So during Tihar, we played Deusi Bhailo in rich people’s neighborhoods to gather money to buy instruments.

Gradually we started getting more opportunities to play music and we started getting better and better at what we did. We were very excited when one time we were invited to play music along with 1974 AD, a pioneer pop band that was one of our sources of inspiration.

Also Watch this: Gorkhali Girls Band performing 1974 AD’s song in a TV show.

Some of my relatives would pass comments to my mother about me playing drums but she would ignore them. My mother was happy to see me happy playing drums and that was more than enough for me. Like my mother, other band member’s parents were also happy about what we were doing. A few years ago, a leading national daily newspaper featured our band. My mother was so happy that she cut out the news piece and framed it. I heard that my other band member’s parents also did the same. It was definitely a proud moment for us, the daughters.

“What do we do after we get married?”

In 2019 our band was successful to release our second song. Our band was making memories and success stories. But one question always loomed in our heads, “What do we do after we get married?” All of us are getting matured. We might get into some circumstances and need to leave a band but I believe if we are strong enough to stay stick with our vision, then we can manage it even after we get married or even in our fifties. We are slowly getting responsibility towards our families. And these responsibilities will add more as we get older. We know that we can’t sustain our life only by making music and it’s a bitter truth. We are also aware that at one point we might need to take a break from band and find jobs for a living. But we will try our best to do music along.

My aim was not to become a drummer. It is a will power that arose while growing up and experiencing gender discrimination. It was my rage against a society that thinks that man can only play music. It was an unintended zeal to do better than boys as I was treated differently for just being a girl. I still ponder about why did my brother had the privilege to go to a decent school and not me? There are deep-rooted inequalities in society and someone has to fight against them and I consider myself to be one. I know it’s not enough but even if it could change like 1 percentage then I’d consider myself successful. The change has to be done here, so since my childhood I never thought of leaving the country. I always wanted to do something in my own country, in my own community.

My aim was not to become a drummer. It is a will power that arose while growing up and experiencing gender discrimination. It was my rage against a society that thinks that man can only play music. It was an unintended zeal to do better than boys as I was treated differently for just being a girl. I still ponder about why did my brother had the privilege to go to a decent school and not me? There are deep-rooted inequalities in society and someone has to fight against them and I consider myself to be one. I know it’s not enough but even if it could change like 1 percentage then I’d consider myself successful. The change has to be done here, so since my childhood I never thought of leaving the country. I always wanted to do something in my own country, in my own community.

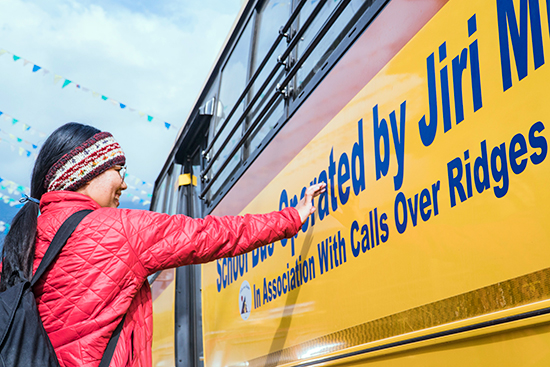

Now, I’m involved in the organization, named Calls Over Ridges, which works for the betterment of the education system in Nepal. I can totally see the need for a good education in our country. I remember going to the government school and the quality of education they provide. But I’m thankful to my parents for sending me to the school, at least, while dealing with so many socio-economic hardships. But I want this scene to change for the upcoming generations, especially the girls. Together with music and advocating for better education, I think I can bring some change to improve the education system of government schools.

which her two oldest daughters were successfully sponsored to attend boarding school and receive a quality education, as well as the necessities of physical care and nourishment.

which her two oldest daughters were successfully sponsored to attend boarding school and receive a quality education, as well as the necessities of physical care and nourishment.