When I was small my father left us. I don’t know where he went. My family members spoke about it in our native Tamang language but since I didn’t know how to speak it, I couldn’t understand where he had gone. So, my mother was both my father and mother. When I was still very young, we left our village and migrated to Kathmandu.

In Kathmandu my mother opened a bhatti. She worked very hard and did very well in her job. When we came home from school, she always fed us delicious snacks. My mother was doing so well, that people would borrow money from her. She helped many from our village who would ask her for some loans. Most of these loans have never been paid back to her.

I still remember that day, when I came back from school and she wasn’t there to serve us any snacks. Me and my little sister looked all over the shop but we couldn’t find her. My aunt came to the shop and took us with her. No-one told me where my mother had gone but I listened to my family members speaking and found out that she had been arrested and taken into jail.

Since my family members only speak our native language, it was very difficult for them to look for my mother. They speak no Nepali and so navigating themselves in Nepal’s bureaucratic system is almost impossible. After few months, the police sent us a message saying that we could meet my mother. She was beaten very badly so she was sick at that time. We took some fruits for my mother. When she saw me and my sister, she hugged us and cried a lot. She shared all the sufferings of jail with my aunt. Since then we started visiting my mother every Saturday.

My aunt took care of us when my mother was in imprisoned. But she had a lot of mouths to feed so it was very difficult for her. She was also taking care of some of my cousins. We were often hungry and would do things for money like going to the construction site and collecting nails. We would then sell the nails and buy dalmot for lunch. During our lunch at school, we would eat the packet of dalmot very slowly since we had no other food. We would also go to forest nearby to collect plastic wrappers and make daalo, which we would sell.

One day, we got word that our mother wanted us to come and stay with her in jail. Perhaps because my aunt was having a hard time taking responsibility for us, they decided we should join our mother. I spent some good time in there with my mother and saw the wounds on her body from when they beat her. She was still in pain from the beatings. I then found out that my mother was in prison for smuggling drugs and that her friend and partner had actually turned her in. I also found out that a few months later her partner was also arrested but she committed suicide in prison.

After a month of being in jail, the jail er told us that we should go stay outside of jail so we could study and have a sort of a normal life.We then met Pushpa mamu who took us and we stayed in a hostel not far away. We would come every weekend to visit our mother. I felt really good whenever I would spend time with my mother. She would cook for us and we would sleep together. I loved the way she cooked food and played with my hair. My mother would also sew clothes, knit sweaters inside jail and earn money that way. She also made new clothes for us during the festivals.

er told us that we should go stay outside of jail so we could study and have a sort of a normal life.We then met Pushpa mamu who took us and we stayed in a hostel not far away. We would come every weekend to visit our mother. I felt really good whenever I would spend time with my mother. She would cook for us and we would sleep together. I loved the way she cooked food and played with my hair. My mother would also sew clothes, knit sweaters inside jail and earn money that way. She also made new clothes for us during the festivals.

Every time I was sad to leave my mother after the weekends were over she would make me feel better by telling me that the jail is her school and in the same way that I had to stay outside and go to school, she had to stay in jail and finish her school. She said she was getting her education in jail but I would be getting my education in school. She was also very protective of us when we spent time with her in jail because there were many women who were mentally not stable. They would often get violent, cause fights and create problems. I would get very scared in prison when the aunties would fight with each other and the police would come and punish them for fighting. The ones who fought would get tied to a big iron wheel with heavy chains.

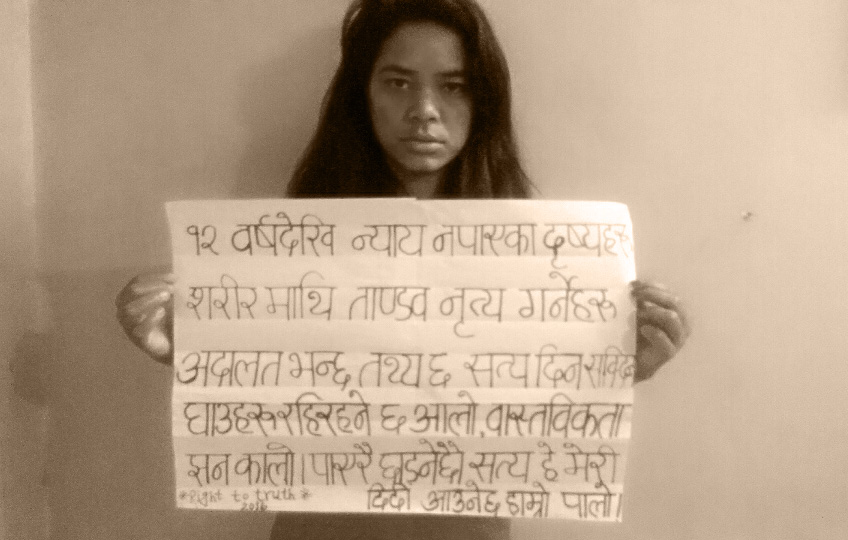

Mother thought she would get free after 4 years but it turned out she was imprisoned for 10 years. During those 10 years she was often beaten very badly. She needed an operation for her uterus once and one of her eye went blind as well. She would save the rice, lentils and grains she got as her ration in prison and instead of eating it she would sell it to the other inmates. She would then send us the money. Because of this, she is now very weak and often sick.

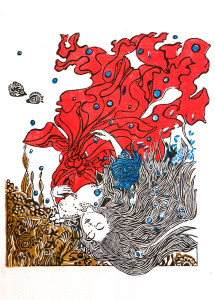

After all these years of separation, now it’s difficult for me to readjust to being with my mother. We have a distance between us because of the 10 year separation. I don’t live with her now even though she is out of prison. I still stay at the Butterfly Home at ECDC because I feel like this is now my home. In the art that I do, I try to show the emotional distance between me and my mother. I feel blessed to have a home like the Butterfly Home and to be able to continue my studies and do what I want in my life.

I do however understand that people will do what they can to feel their children. It’s poverty that made my mother desperate and I know she tried very hard to be a good mother and take care of us to the best of her ability.

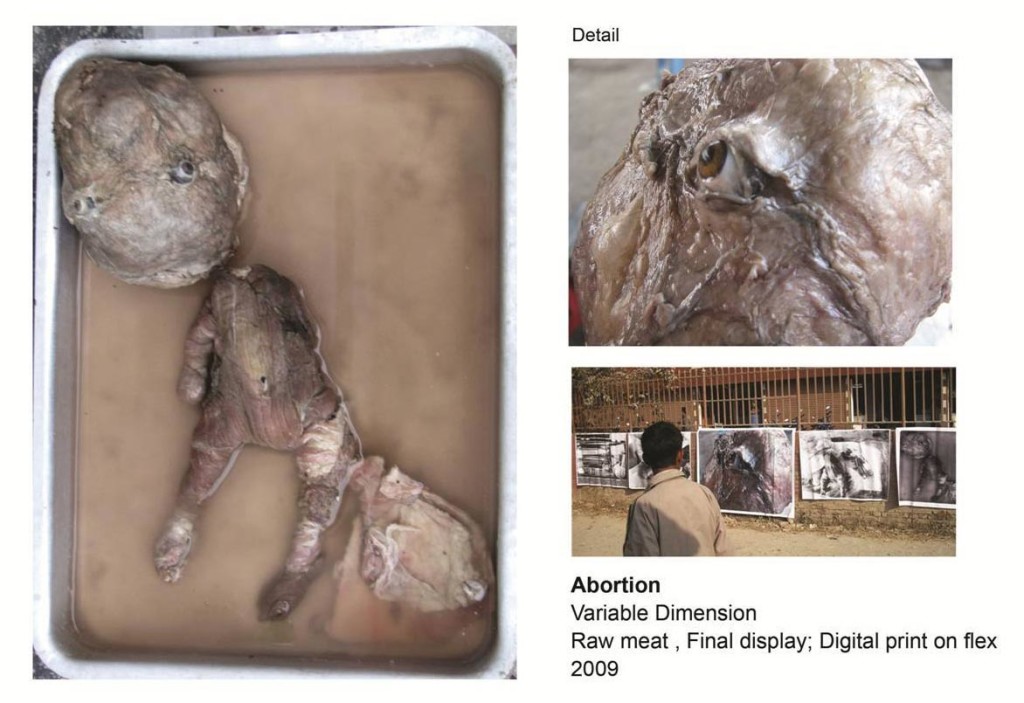

Fine arts has always been something that I have been interested in. Initially I thought I wanted to study math and be a banker so I would be able to make lots of money for my family, but when I consulted Pushpa mamu at ECDC she reminded me that money is not everything. To be able to do what you love in life is more precious than anything else. So, after finishing high school, I asked her to enroll me in the Fine Arts Program at Kathmandu University where I am studying now.Here, I can share my ideas and things that stress me with my mentor and friends. We often talk about emotions, and how out expression relieves our stress so I think this has been the best decision in my life. Studying art has taught me a lot about myself.

Various family members would often try to put pressure on me by telling me that everyone else my age was earning money and supporting their families but my mother has continually supported me. She says to me, if they are earning money then you are earning knowledge. So don’t listen to them and focus on your studies.

I want to study art therapy in the future. Although I love to paint and make my own work I don’t see the value of staying alone and painting my whole life. I want my skills to help other people, just like my mother and all the other aunties in jail who had immense stress, mental instability and various illnesses. I want to spend my life as an art therapist in prison and I know that Pushpa mamu and ECDC will make this possible for me.

My mother reminds me that everything happens for a reason. Even when bad things happen, there is something good that comes out of it. I feel very fortunate to be a part of the family that I now call my own. If I hadn’t gotten a chance to stay here, who knows, maybe I would be one of the thousands of young girls working in the Gulf. When we go back to my village, people are proud of me and appreciate that I am so focused on my studies. Even though my mother suffered a lot, she ended up creating a life for us that is a very good life.

My mother reminds me that everything happens for a reason. Even when bad things happen, there is something good that comes out of it. I feel very fortunate to be a part of the family that I now call my own. If I hadn’t gotten a chance to stay here, who knows, maybe I would be one of the thousands of young girls working in the Gulf. When we go back to my village, people are proud of me and appreciate that I am so focused on my studies. Even though my mother suffered a lot, she ended up creating a life for us that is a very good life.

I am very thankful that I didn’t spend my childhood wasting my time but actually learnt how to struggle since very early on. My struggle is my strength now. I know that I am making my own way and that everything will be good.

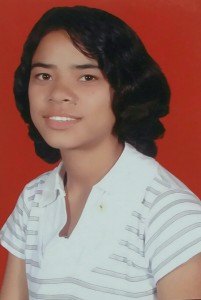

My name is Laxmi Tamang. I live at the Butterfly Home which is run by Early Childhood Development Center. I am currently an arts student at Kathmandu University’s Fine Arts Program. I am an aspiring artist. And this is my story.

***

I learnt about forming a union. The management never provided us with any security so this was the only way we could help each other. All the employees formed a union. We got an identity card saying that we are dance bar employees. When the owner of the dance bar found out that we formed a union he called for a meeting at midnight after work. We told him that we needed a union for our security. I reminded him that when the police beat us, I wasn’t compensated a penny for medical expenses. There was a heated argument and our boss wanted to fire all 60 employees of the bar along with us if we continue forming union groups. WOFOWON helped us negotiate with our bosses and finally we all returned to working in the same place.

I learnt about forming a union. The management never provided us with any security so this was the only way we could help each other. All the employees formed a union. We got an identity card saying that we are dance bar employees. When the owner of the dance bar found out that we formed a union he called for a meeting at midnight after work. We told him that we needed a union for our security. I reminded him that when the police beat us, I wasn’t compensated a penny for medical expenses. There was a heated argument and our boss wanted to fire all 60 employees of the bar along with us if we continue forming union groups. WOFOWON helped us negotiate with our bosses and finally we all returned to working in the same place.

My family were farmers but didn’t have their own land so we all worked in other people’s land. But I never did any heavy work. It was very difficult for me to plough and do the heavy stuff. I preferred cooking food and bringing it to the workers in the fields. This was usually what women did. I used to wash dishes, carry fertilizers and do all the house work which men didn’t do. I always was found with a group of girls and I disliked boys. The boys used to tease me telling me that I was like a girl. But at the same time I felt that I was attracted to them. It was a strange thing.

My family were farmers but didn’t have their own land so we all worked in other people’s land. But I never did any heavy work. It was very difficult for me to plough and do the heavy stuff. I preferred cooking food and bringing it to the workers in the fields. This was usually what women did. I used to wash dishes, carry fertilizers and do all the house work which men didn’t do. I always was found with a group of girls and I disliked boys. The boys used to tease me telling me that I was like a girl. But at the same time I felt that I was attracted to them. It was a strange thing.

I am modeling and also have been writing as a journalist for Himalayan News Express Online. I take interviews of celebrities.

I am modeling and also have been writing as a journalist for Himalayan News Express Online. I take interviews of celebrities. I have seen many cases of trans men and women where the families are around until we send them money. And a lot of this money is earned working in Thamel since there are barely any opportunities for us. When we reach a certain age and cannot work anymore our families have often discarded us. So many people from my community commit suicide. So many are found dead on the streets. But then there are those like Bhumika Shrestha who is well known politically, Anjali Lama who is a famous model and Sophie Sunwar who has her own make up studio.

I have seen many cases of trans men and women where the families are around until we send them money. And a lot of this money is earned working in Thamel since there are barely any opportunities for us. When we reach a certain age and cannot work anymore our families have often discarded us. So many people from my community commit suicide. So many are found dead on the streets. But then there are those like Bhumika Shrestha who is well known politically, Anjali Lama who is a famous model and Sophie Sunwar who has her own make up studio.

I had never thought of changing my last name after marriage. Neither me nor my husband care about it but we get so much pressure from our communities about it. I cannot understand how legally women are made to identify with the men in their lives. This entire system is setup to make women inferior than men. Maybe I never had thought about it seriously before but now it haunts me to realize that after birth we are identified by our father’s name and then by our husband’s name.

I had never thought of changing my last name after marriage. Neither me nor my husband care about it but we get so much pressure from our communities about it. I cannot understand how legally women are made to identify with the men in their lives. This entire system is setup to make women inferior than men. Maybe I never had thought about it seriously before but now it haunts me to realize that after birth we are identified by our father’s name and then by our husband’s name.

I started doing community work, working in schools, the community forest etc. I immersed myself in the party’s work and community work. My children were provided with scholarships. I got a small fund of 100$ for cattle farming. I had to manage my time with household work, farming, meetings and political work. During that time, we raised issues of women’s rights, Dalit and indigenous people’s rights and fought for it with our lives.

I started doing community work, working in schools, the community forest etc. I immersed myself in the party’s work and community work. My children were provided with scholarships. I got a small fund of 100$ for cattle farming. I had to manage my time with household work, farming, meetings and political work. During that time, we raised issues of women’s rights, Dalit and indigenous people’s rights and fought for it with our lives.

After passing my SLC in 1999 I came to Kathmandu. I was unfamiliar with it and it was scary for me. The first time I was in Ratnapark, I saw many disabled and helpless people. I felt bad for them and used to give them all my travel fare and walked home instead.

After passing my SLC in 1999 I came to Kathmandu. I was unfamiliar with it and it was scary for me. The first time I was in Ratnapark, I saw many disabled and helpless people. I felt bad for them and used to give them all my travel fare and walked home instead.

While I was in training at the school I bagged first prize among 25 people. That is when I realized that I would make a career in tailoring, pursue it to the next level and support my family with it. I perfected myself by practising on clothes of people without charging them. I worked in a boutique for a short period of time. After sometime my neighbor informed me about an organization called Hausala Creatives. They provide co-working space, create handmade items, encourage craftsmanship, and empower women. I joined the organization and here I am today pursuing my career in tailoring. I have been using mainly Dhaka as a material to make all our products since it gives a traditional touch and is popular in the market as a typical Nepali product. Dhaka has been my main focus because I want to promote traditional Nepali fabrics in the products.

While I was in training at the school I bagged first prize among 25 people. That is when I realized that I would make a career in tailoring, pursue it to the next level and support my family with it. I perfected myself by practising on clothes of people without charging them. I worked in a boutique for a short period of time. After sometime my neighbor informed me about an organization called Hausala Creatives. They provide co-working space, create handmade items, encourage craftsmanship, and empower women. I joined the organization and here I am today pursuing my career in tailoring. I have been using mainly Dhaka as a material to make all our products since it gives a traditional touch and is popular in the market as a typical Nepali product. Dhaka has been my main focus because I want to promote traditional Nepali fabrics in the products.

Three dollars each for monthly school fees makes it six dollars a month for two which is already a big amount for us and with academic competition on the rise extra tuition classes are a must. We can only afford to pay three dollars for one and two dollars for another. We chose the second for our son since he is the youngest and probably needs more guidance but it breaks my heart when my little daughter asks if it is true that we didn’t send her for tuition because she is a girl and is the less preferred one.

Three dollars each for monthly school fees makes it six dollars a month for two which is already a big amount for us and with academic competition on the rise extra tuition classes are a must. We can only afford to pay three dollars for one and two dollars for another. We chose the second for our son since he is the youngest and probably needs more guidance but it breaks my heart when my little daughter asks if it is true that we didn’t send her for tuition because she is a girl and is the less preferred one.