I was born in Hasuliya village of Kailali district in Far Western Nepal. I am a Tharu – indigenous to the land where I was born. I grew up with my mother, grandmother and two younger brothers. My father was one of the founding member of then Nepal Communist Party (Maoist) in Kailali district. I have a vague memory of him. I remember him staying far from our home and would visit us at times. The army and police would often come to our house looking for my father. Not been able to find him, the authorities would give us all a very hard time. He stopped coming home that often. After a while he went underground.

My father had a pharmacy. We don’t know when and how he got involved in the communist party, the then banned outfit. After both my father and uncle joined the party and left home, my grandfather took over the responsibilities of our home. My grandfather was a peasant. He had to struggle a lot to make sure I got educated.

The Nepal army would come and torture us all quite frequently. One day, the police took my grandfather and beat him inhumanely. He died with his severely wounded body as he wasn’t taken to the hospital on time. After his death, my family went through major financial crisis. My mother and grandmother did not know how to read or write. They only spoke our native Tharu language and did not speak Nepali. Due to the immense stress they couldn’t work much. But somehow, they managed to continue sending me to school.

On June 11th, 2001 we got informed by the party that my father died in an incident. We never saw his dead body. The Maoist party completed his funeral and lots of people told me that they saw my father’s dead body but I still don’t believe it. I feel that one day he will return home. I keep seeing him in my dreams too.

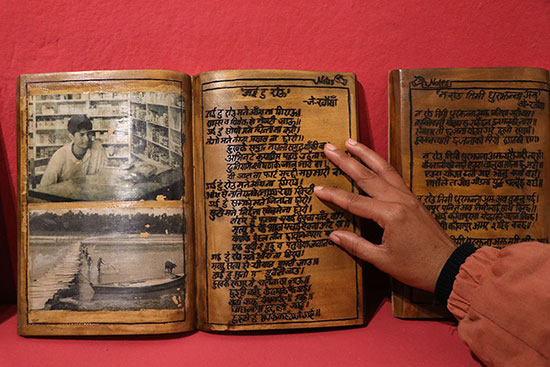

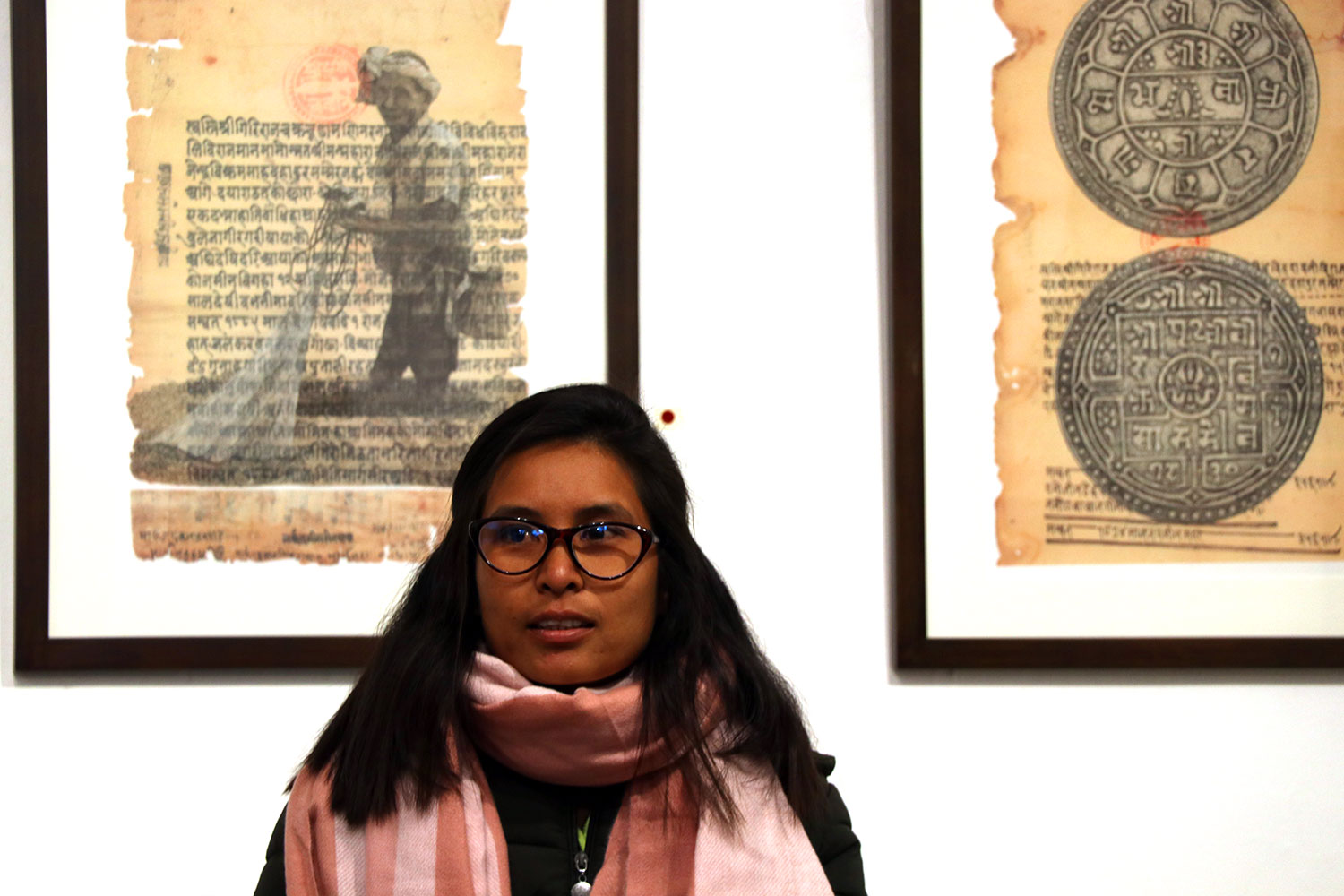

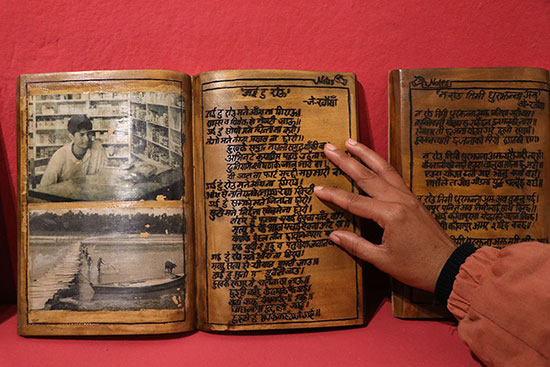

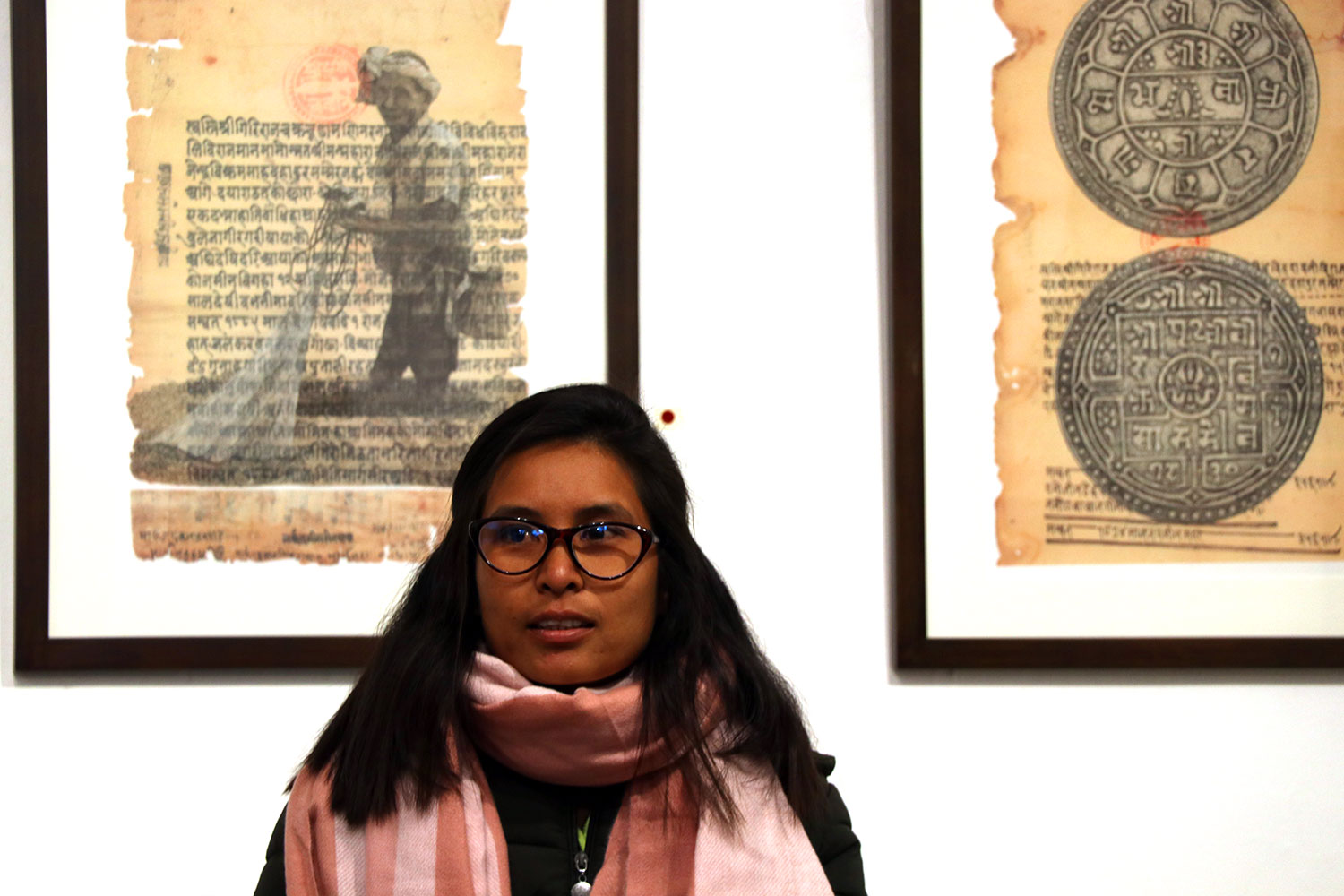

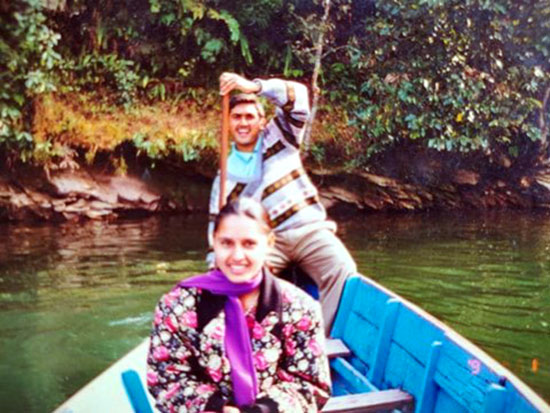

- Indu looking at her father’s photo in a hand-carved diary exhibited at Lavkant Chaudhary’s recent solo art exhibition.

After a few months, my uncle was also brutally killed by the police force in one of the raids. He had also joined the underground party. Basically he had no choice than to join the party because of all the torture he would get from the authorities for being a brother of a Maoist. We did not see his dead body either. His wife was pregnant at the time.

Life became very difficult for us. The ten years long People’s War engulfed all the breadwinners of my family; my grandfather, my father and my uncle.

I used to be a very good student as a child but after losing my family members I stopped focusing on my studies. My entire family went through severe depression. Three women in my family lost their husbands in a short span of time, one after another. My friends stopped playing with me because my father was labelled a terrorist. Our society literally stopped interacting with our family. We were socially outlawed. All the remaining members of our family went through mental and physical trauma.

When my father was still alive he told me a few things. His dream was to change the system. He would tell me how the Tharu people have been historically oppressed in Nepal. He made me understand the concept of Kamaiya and Kamlari practices. He showed me how we were discriminated against through the food we eat. In my childhood, it was humiliating when someone called us rat-eaters.

My father and uncle dreamt of federalism, of creating a Tharuwaan state for the Tharu people. Now, after all those years, the same Maoists are part of the government but still the Tharu people are oppressed every single day.

My father published a monthly magazine “Muktik Dagar” (means: a freedom path) with revolutionary songs, poems, and articles in Tharu language. During the war times, people would get arrested for just having that magazine in their house. People would immediately dump or burn it in fear of police raids. After my father’s death it stopped being published. I still remember many soulful revolutionary poems and articles published on that magazine.

After years of struggle, I also started becoming very politically active in 2005. I was actively involved in the movement to get rid of the king in 2006 and then in the Tharuhat movement since 2007. I was the treasurer of the Tharuhat Tharuwaan Committee. Back then, the Tharus were put in the same category as Madhesi. We began our movement for our own identity. We demanded proportional representation and a Tharuhat autonomous state but none of our demands were addressed. I was young back then, just out of school.

In 2015 we started another Tharuhat movement. It was heavily repressed by the state. The police went around arresting every male who was involved in the movement and attacking every Tharu house. So, we made a strategy to protect our movement and women took over and led the movement. We wore our traditional clothes and protested in the streets of Dhangadi for weeks. We started celebrating our traditional festivals. In retrospect, by these actions at least we managed to save our clothes and culture. We also started lobbying for our native language to be taught in schools and to make it an official language in the government office procedures.

We were organizing a mass conference where many activists from around the country was supposed to participate. The supporters of Akhanda Sudur Paschim – people who were opposed to our idea of autonomous Tharuwan – stopped villagers and participants to reach our venue in Dhangadi. They started pelting stones and blocking roads. Many participants from Tikapur who were coming to our conference also got stopped on the way by this group who started voicing against our movement. Many people were injured. After our mass conference, they then organized a motorcycle rally but the people of Tikapur didn’t let them pass. With the help of the police and local authorities, they started attacking us. They beat, torture and gave Tharu people a very hard time. They burnt our homes and offices, vandalized properties owned by Tharus. It was a one big systematic attack targeted against our community to silence our movement.

On 24 August, 2015, we had a program demanding an autonomous Tharuhat State in Dhangadi. Me along with other Tharu activists went to put a banner in front of the Chief District Office. Meanwhile the Tikapur massacre happened. We were protesting and heading our rally towards the CDO. After a moment we got a call from Tikapur that many people were killed while demonstrating. Then, we decided to turn back.

There are many reports of Tikapur massacre, including report by Amnesty International, but the government didn’t publish any reports. They refuse to acknowledge the loss of Tharu lives caused in the massacre. Tharu people also started getting severely oppressed by the state repeatedly. Police would go around arresting people again. People fled their homes and started hiding in the fields. We were not even allowed to go catch fish. Our daily lives are linked with fish, it being a basic diet in our culture. Not allowing us to do our daily chores was definitely a major human rights abuse.

For me, that was a realizing moment, that I could not go much further politically without being totally destroyed by the repression. So, like my father, I picked up my pen and started to write.

I started writing articles on Tharu identity, women’s rights and other socio-political issues. I then joined Democracy Research Center as a researcher. With some of the money that I got from my job, I did something which I’ve been always meaning to do it since I was young.

After twelve years, I re-published “Muktik Dagar” in my own editorial, in memory of my father. For me, despite of all the state repressions and all those failed attempts at independence, Tharus will continue walking the road to freedom.

मामाघरको हजुरबुबा बिरामी हुनु भएको कारण हामी लकडाउन सुरु हुनु भन्दा पहिला नै मामा घरमा जाने कुरा थियो । जाने भन्दाभन्दै लकडाउन भयो । यहि बीचमा हजुर बुबाको निधन भएको खबर आयो । लकडाउनको कारण हजुरबुबाको अन्तिम मुख र्हेर्न पनि पाएनौं । केही गरि हामी मामाघर गए पनि १४ दिन क्वारेन्टाईनमा बस्नु पर्ने भएकोले नजाने निर्णय ग¥यौं । ममीले हामी कसैलाई नछोई जुठो बार्नु भयो । त्यति बेला असाध्यै नरमाईलो लागेको थियो । यसो सोचें, क्वारेन्टाईन बस्नेहरु र उनीहरुको परिवारजनको हालत कस्तो हुँदो होला?

मामाघरको हजुरबुबा बिरामी हुनु भएको कारण हामी लकडाउन सुरु हुनु भन्दा पहिला नै मामा घरमा जाने कुरा थियो । जाने भन्दाभन्दै लकडाउन भयो । यहि बीचमा हजुर बुबाको निधन भएको खबर आयो । लकडाउनको कारण हजुरबुबाको अन्तिम मुख र्हेर्न पनि पाएनौं । केही गरि हामी मामाघर गए पनि १४ दिन क्वारेन्टाईनमा बस्नु पर्ने भएकोले नजाने निर्णय ग¥यौं । ममीले हामी कसैलाई नछोई जुठो बार्नु भयो । त्यति बेला असाध्यै नरमाईलो लागेको थियो । यसो सोचें, क्वारेन्टाईन बस्नेहरु र उनीहरुको परिवारजनको हालत कस्तो हुँदो होला? यस्तो अवस्थामा नेपालको सिमा मिचेको समाचारहरु पढें । सिमाना मिचिनु जस्तो घटना निकै नरमाईलो लागेको छ । लिपुलेक, कालापानी र सगरमाथा हाम्रो हो जस्ता कुराहरुले मेरो दिमाग घुमाउन थालेको छ । चीन र भारत दुवै मिलेर नेपाललाई खोक्रो बनाउन लागेको झैं लागी रहेको छ तर ३ जेठ २०७७ बिहानको समाचारले मलाई धेरै राम्रो लाग्यो । नेपालको राष्ट्रपतिले भने अनुसार अब नेपालको नयाँ नक्सा निर्माण हुने छ । नेपालको आफ्नै उपग्रह हेर्न पाउने कुराले निकै राम्रो लाग्यो । समाचार पढेपछि मेरो चिन्ता अलि कम भएको छ । के साँच्चै मेरो चिन्ता कम होला त?

यस्तो अवस्थामा नेपालको सिमा मिचेको समाचारहरु पढें । सिमाना मिचिनु जस्तो घटना निकै नरमाईलो लागेको छ । लिपुलेक, कालापानी र सगरमाथा हाम्रो हो जस्ता कुराहरुले मेरो दिमाग घुमाउन थालेको छ । चीन र भारत दुवै मिलेर नेपाललाई खोक्रो बनाउन लागेको झैं लागी रहेको छ तर ३ जेठ २०७७ बिहानको समाचारले मलाई धेरै राम्रो लाग्यो । नेपालको राष्ट्रपतिले भने अनुसार अब नेपालको नयाँ नक्सा निर्माण हुने छ । नेपालको आफ्नै उपग्रह हेर्न पाउने कुराले निकै राम्रो लाग्यो । समाचार पढेपछि मेरो चिन्ता अलि कम भएको छ । के साँच्चै मेरो चिन्ता कम होला त?

She holds a provisional Australian PR which requires her to be in Australia for a substantive time of the year. This year, she has been in Nepal longer than planned and if she does not enter Australia by mid April, there are nominal chance of she getting a PR. This is one of the reason why her family wanted her to return to Australia by March end. However, on each reminder, she told us off with ‘I know all of that. I have it all scheduled.’ I am a non-interfering ‘it’s your choice’ and ‘don’t come to me later’ individual, therefore, I just watched on. Besides, if her family’s emphasis, and mercurial change in Australian government’s lockdown plan would not prompt her, my attempts to inform her would also not be listened to. It is not that I did not try. I did and I failed.

She holds a provisional Australian PR which requires her to be in Australia for a substantive time of the year. This year, she has been in Nepal longer than planned and if she does not enter Australia by mid April, there are nominal chance of she getting a PR. This is one of the reason why her family wanted her to return to Australia by March end. However, on each reminder, she told us off with ‘I know all of that. I have it all scheduled.’ I am a non-interfering ‘it’s your choice’ and ‘don’t come to me later’ individual, therefore, I just watched on. Besides, if her family’s emphasis, and mercurial change in Australian government’s lockdown plan would not prompt her, my attempts to inform her would also not be listened to. It is not that I did not try. I did and I failed. Things got worse when the lockdown happened, and major part of it was set in the kitchen. My cooking cannot appeal everyone. My food easily tastes bland to many of us who like to use generous amount of spices, condiments and oil. Therefore, my grand aunt began to cook and though I had no problems with it, slowly issues around rationing, portion, sourcing of food – be it fresh or dried, or packed – began to emerge. I have always been viewed as the ‘frugal’ one by my family whenever I have stretched use of every substance that is in my possession, including food. Soon, I started to eat leftovers from each meal, silently fume over the rationing, and get appalled at she going out every morning to buy ‘fresh’ vegetables and meat. This was also amplified by the fact that another adult living with us – father of my child – has his own taste and was no better than my grand aunt. In the first week of lockdown, I witnessed polite struggle of these two with one other, in the kitchen. Interestingly, both of them had agreed (no words spoken here) that it should be these two who should cook.

Things got worse when the lockdown happened, and major part of it was set in the kitchen. My cooking cannot appeal everyone. My food easily tastes bland to many of us who like to use generous amount of spices, condiments and oil. Therefore, my grand aunt began to cook and though I had no problems with it, slowly issues around rationing, portion, sourcing of food – be it fresh or dried, or packed – began to emerge. I have always been viewed as the ‘frugal’ one by my family whenever I have stretched use of every substance that is in my possession, including food. Soon, I started to eat leftovers from each meal, silently fume over the rationing, and get appalled at she going out every morning to buy ‘fresh’ vegetables and meat. This was also amplified by the fact that another adult living with us – father of my child – has his own taste and was no better than my grand aunt. In the first week of lockdown, I witnessed polite struggle of these two with one other, in the kitchen. Interestingly, both of them had agreed (no words spoken here) that it should be these two who should cook.

लकडाउन लम्बिदै जाँदा मेरा साथिहरु बिस्तारै अब त घर बस्ने बानी पर्यो भन्दैथे । मलाई चाही बिस्तारै घरको बसाई अत्यास लाग्दो बन्दै गएँको भान भईरहेको थियो । मेरा साथिहरुले जस्तै गरि मैले पनि घरको बसाईलाई सहज पार्नै सकिन । मेरा साथिहरुलाई पढ्ने, आर्ट गर्ने, योगा गर्ने, नयाँ परिकार पाकाउने, विभिन्न रिसर्च गर्ने, बानी परेको थियो । मलाई भने परिवारका सदस्यको टाईमटेवलको बानी परेको थियो । घरको कामको चापले अफिसको कामहरु समयमा पुरा गर्न नसक्दा मलाई एकदम धेरै पीडा हुन्थ्यो ।

लकडाउन लम्बिदै जाँदा मेरा साथिहरु बिस्तारै अब त घर बस्ने बानी पर्यो भन्दैथे । मलाई चाही बिस्तारै घरको बसाई अत्यास लाग्दो बन्दै गएँको भान भईरहेको थियो । मेरा साथिहरुले जस्तै गरि मैले पनि घरको बसाईलाई सहज पार्नै सकिन । मेरा साथिहरुलाई पढ्ने, आर्ट गर्ने, योगा गर्ने, नयाँ परिकार पाकाउने, विभिन्न रिसर्च गर्ने, बानी परेको थियो । मलाई भने परिवारका सदस्यको टाईमटेवलको बानी परेको थियो । घरको कामको चापले अफिसको कामहरु समयमा पुरा गर्न नसक्दा मलाई एकदम धेरै पीडा हुन्थ्यो । घरमा यस्ता स–साना टिप्पणी हुँदै जाँदा मलाई कताकता उकुसमुकुस भए जस्तो लाग्यो । मैले श्रीमानलाई सेयर गरे उसले यस्ता कुरा सुन्नु हुन्न एक कानले सुन्ने अर्को कानले उडाउने अहिले हाम्रो सुन्ने पालो हो हाम्रो पालो आउँछ अनि भनौंला भन्यो । मेरो कामको बारेमा पहिले पनि कुरा हुने गर्थ्यो र पहिले पनि उसले यस्तै भन्थ्यो । त्यती बेला त म अफिस जान्थें, साथिहरुसँग भेट्थें, साथिहरुसँग कुरा सेयर गर्थे, केही हल्का हुन्थ्यो। नयाँ काममा लाग्थें। बेलुका घर जाँदा यी सबै कुरा भुलेको हुन्थ्यो र ति सब दिनहरूमा यस्ता कुरा सायद मलाई सहज भएको थियो । तर अहिले त्यस्तो छैन – घरको चार पर्खाल भित्र हामी बन्दि जो भएका छौं । बन्दमा मेरो मनका चोट र भावना सबै बन्द भएको छ जसले मलाई भित्रभित्रै पोलिरहेछ ।

घरमा यस्ता स–साना टिप्पणी हुँदै जाँदा मलाई कताकता उकुसमुकुस भए जस्तो लाग्यो । मैले श्रीमानलाई सेयर गरे उसले यस्ता कुरा सुन्नु हुन्न एक कानले सुन्ने अर्को कानले उडाउने अहिले हाम्रो सुन्ने पालो हो हाम्रो पालो आउँछ अनि भनौंला भन्यो । मेरो कामको बारेमा पहिले पनि कुरा हुने गर्थ्यो र पहिले पनि उसले यस्तै भन्थ्यो । त्यती बेला त म अफिस जान्थें, साथिहरुसँग भेट्थें, साथिहरुसँग कुरा सेयर गर्थे, केही हल्का हुन्थ्यो। नयाँ काममा लाग्थें। बेलुका घर जाँदा यी सबै कुरा भुलेको हुन्थ्यो र ति सब दिनहरूमा यस्ता कुरा सायद मलाई सहज भएको थियो । तर अहिले त्यस्तो छैन – घरको चार पर्खाल भित्र हामी बन्दि जो भएका छौं । बन्दमा मेरो मनका चोट र भावना सबै बन्द भएको छ जसले मलाई भित्रभित्रै पोलिरहेछ ।

म : वास्तवमा आजसम्म मैले आफूलाई अनुशासनमा राख्न सकेको रहेनछु । म बाहिर जति धेरै दिनहरु बिताउन सक्छु । त्यति घरमा समय बिताउन म सक्षम छैन र मलाई आफ्नै घर बन्दि गृह जस्तो हुनेछ भन्ने मैले सोचेकै थिईन । लकडाउनको केहि दिन मलाई रमाईलो लाग्यो । घरमा समय दिन नसकेको र आफ्नो लागि समय नभए जस्तो बल्ल मैले मेरो लागि समय पाए भने जस्तो लागेको थियो । तर बिस्तारै आफै बसेको घर आफूलाई जन्म दिने आमाबुबा आफ्ना साथी भाईहरुसँग घुलमिल हुन नै मलाई आफैसँग संघर्ष गर्नु प¥यो । म यतिसम्म घरबाट टाढा भएको रहिछु कि मलाई केही दिन पछि मलाई मेरो घरको मान्छे नै बढी भए जस्तो लाग्यो । त्यसको परिणाम स्वरुप विस्तारै मलाई रिस उठने, आफूले भनेको कुरा मात्र हुनपर्छ जस्तो धारणा राख्ने, कोहीसँग बोल्न मन नलाग्ने, नखाने र आफूलाई एक्लोपनाको अनुभुति भयो । सबै सकियो जस्तो अनुभुति हुन थाल्यो । तर विस्तारै आफूलाई नै अनुशासनमा राख्ने कोशीस गरेँ वा गर्दैछु । यो बिचमा आफूलाई कसरी व्यवस्थित राख्ने? भनेर केही कोशीसहरु गरँे जस्तै ः कोहीसँग नबोल्ने, आफूलाई कोठामा बन्द गर्ने, किताब पढ्ने, आफूलाई लागेको लेख्ने, फिल्महरु हेर्ने साथीसँग कुरा गर्ने कोरोनाको न्यूज पढ्न बन्द गर्ने । आफूलाई सकेसम्म व्यस्त राख्ने जस्ता कार्यले मलाई कोरोनाको महामारीसँग लड्ने शक्ति दिएको जस्तो लाग्छ ।

म : वास्तवमा आजसम्म मैले आफूलाई अनुशासनमा राख्न सकेको रहेनछु । म बाहिर जति धेरै दिनहरु बिताउन सक्छु । त्यति घरमा समय बिताउन म सक्षम छैन र मलाई आफ्नै घर बन्दि गृह जस्तो हुनेछ भन्ने मैले सोचेकै थिईन । लकडाउनको केहि दिन मलाई रमाईलो लाग्यो । घरमा समय दिन नसकेको र आफ्नो लागि समय नभए जस्तो बल्ल मैले मेरो लागि समय पाए भने जस्तो लागेको थियो । तर बिस्तारै आफै बसेको घर आफूलाई जन्म दिने आमाबुबा आफ्ना साथी भाईहरुसँग घुलमिल हुन नै मलाई आफैसँग संघर्ष गर्नु प¥यो । म यतिसम्म घरबाट टाढा भएको रहिछु कि मलाई केही दिन पछि मलाई मेरो घरको मान्छे नै बढी भए जस्तो लाग्यो । त्यसको परिणाम स्वरुप विस्तारै मलाई रिस उठने, आफूले भनेको कुरा मात्र हुनपर्छ जस्तो धारणा राख्ने, कोहीसँग बोल्न मन नलाग्ने, नखाने र आफूलाई एक्लोपनाको अनुभुति भयो । सबै सकियो जस्तो अनुभुति हुन थाल्यो । तर विस्तारै आफूलाई नै अनुशासनमा राख्ने कोशीस गरेँ वा गर्दैछु । यो बिचमा आफूलाई कसरी व्यवस्थित राख्ने? भनेर केही कोशीसहरु गरँे जस्तै ः कोहीसँग नबोल्ने, आफूलाई कोठामा बन्द गर्ने, किताब पढ्ने, आफूलाई लागेको लेख्ने, फिल्महरु हेर्ने साथीसँग कुरा गर्ने कोरोनाको न्यूज पढ्न बन्द गर्ने । आफूलाई सकेसम्म व्यस्त राख्ने जस्ता कार्यले मलाई कोरोनाको महामारीसँग लड्ने शक्ति दिएको जस्तो लाग्छ । घरपरिवार, छिमेकी र समाज : यो बिचमा मैले मेरो घर परिवार र समाजलाई अध्ययन गर्ने अवसर पाएको छु । मेरो अध्ययनले पाएको सामाज आफूलाई अनुशासनमा राख्न जति गाह्रो छ, त्यो भन्दा बढी समाज परिवारलाई राख्न गाह्रो छ । सबैको आ—आफ्नो धारणा हुन्छ विचार हुन्छ । जुन कहिल्यै हाम्रो ध्यान नपुगको वा हामीलाई त्यस्ता विषयमा कुरा गर्न समय नभएको विषय — के खाने? कुन फिल्म हेर्ने? जस्तो विषय पनि धेरै सँगै बसेपछि र अन्य काम नभएपछि यस्ता विषयमा छिमेकीमा झगडा भएको देखे । घरमा धेरै व्यक्तिहरुसँगै घर बस्दा घरेलु हिंसा बढेको पनि देखियो । झगडाको विषयः श्रीमानले बाहिरको व्यक्तिहरु ल्याएर तास खेल्ने वा खेल्न जाने, पानीको अभाव, खाना कसले बनाउने?, पैसाको अभाव हुँदै जाने जस्ता विषयले पनि झगडाको विषय बन्ने र यस्ता विषयले ठुलो रुप लिएको देखियो ।

घरपरिवार, छिमेकी र समाज : यो बिचमा मैले मेरो घर परिवार र समाजलाई अध्ययन गर्ने अवसर पाएको छु । मेरो अध्ययनले पाएको सामाज आफूलाई अनुशासनमा राख्न जति गाह्रो छ, त्यो भन्दा बढी समाज परिवारलाई राख्न गाह्रो छ । सबैको आ—आफ्नो धारणा हुन्छ विचार हुन्छ । जुन कहिल्यै हाम्रो ध्यान नपुगको वा हामीलाई त्यस्ता विषयमा कुरा गर्न समय नभएको विषय — के खाने? कुन फिल्म हेर्ने? जस्तो विषय पनि धेरै सँगै बसेपछि र अन्य काम नभएपछि यस्ता विषयमा छिमेकीमा झगडा भएको देखे । घरमा धेरै व्यक्तिहरुसँगै घर बस्दा घरेलु हिंसा बढेको पनि देखियो । झगडाको विषयः श्रीमानले बाहिरको व्यक्तिहरु ल्याएर तास खेल्ने वा खेल्न जाने, पानीको अभाव, खाना कसले बनाउने?, पैसाको अभाव हुँदै जाने जस्ता विषयले पनि झगडाको विषय बन्ने र यस्ता विषयले ठुलो रुप लिएको देखियो ।

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about other concerns about the pandemic. What will our lives be like after the quarantine gets lifted? We will have to work through this “quarantine state of mind” we have adapted to and it will take weeks if not months. I was reading an article where David Spigel, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University said, “ We are training people to see the world as a dangerous place. This invisible enemy could be anywhere.” Interacting with anyone other than the immediate family members won’t be easy, say your interaction with your shopkeeper, bank teller, barber because we now have been trained to view them as potential carriers. Another major concern I have as a student of Clinical Psychology is that I think people will develop agoraphobia, where some people refuse to leave their homes. Mask was always a major part of our lifestyle but now it will become a wardrobe staple.

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about other concerns about the pandemic. What will our lives be like after the quarantine gets lifted? We will have to work through this “quarantine state of mind” we have adapted to and it will take weeks if not months. I was reading an article where David Spigel, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University said, “ We are training people to see the world as a dangerous place. This invisible enemy could be anywhere.” Interacting with anyone other than the immediate family members won’t be easy, say your interaction with your shopkeeper, bank teller, barber because we now have been trained to view them as potential carriers. Another major concern I have as a student of Clinical Psychology is that I think people will develop agoraphobia, where some people refuse to leave their homes. Mask was always a major part of our lifestyle but now it will become a wardrobe staple.

घर वरपर लकडाउन भएको जस्तो वातावरण नै थिएन । पहिला जस्तै थियो तर अहिले पुरुषको दैनिकीमा मात्र फरक देखिएको छ । लकडाउन पछि कामहरु सबै बन्द भएपछि प्राय पुरुषहरु फ्रि छन् । त्यसैले एक हुल बनाएर कोही जनचेतनाका लागि गाउँ टोल टोलमा गएर माइकिङ्ग गर्थे त कोही कि तास खेल्थे कि खसी खोज्न हिड्थे । ठेचोका प्राय महिलाहरु गलैचा बुन्ने र खेतीपातीको काम गर्छन् । अहिले लकडाउनका कारण अर्डर आउन बन्द भएपछि अहिले उहाँहरु घरायसी काम र खेतीपातीमा व्यस्त हुनुहुन्छ । वास्तवमा भन्नुपर्दा महिलाहरुलाई लकडाउनको बेलामा पनि दैनिक जीवनमा केही परिवर्तन आएको छैन ।

घर वरपर लकडाउन भएको जस्तो वातावरण नै थिएन । पहिला जस्तै थियो तर अहिले पुरुषको दैनिकीमा मात्र फरक देखिएको छ । लकडाउन पछि कामहरु सबै बन्द भएपछि प्राय पुरुषहरु फ्रि छन् । त्यसैले एक हुल बनाएर कोही जनचेतनाका लागि गाउँ टोल टोलमा गएर माइकिङ्ग गर्थे त कोही कि तास खेल्थे कि खसी खोज्न हिड्थे । ठेचोका प्राय महिलाहरु गलैचा बुन्ने र खेतीपातीको काम गर्छन् । अहिले लकडाउनका कारण अर्डर आउन बन्द भएपछि अहिले उहाँहरु घरायसी काम र खेतीपातीमा व्यस्त हुनुहुन्छ । वास्तवमा भन्नुपर्दा महिलाहरुलाई लकडाउनको बेलामा पनि दैनिक जीवनमा केही परिवर्तन आएको छैन ।

As a child, I always wanted to study and become educated so that I would have the same opportunities as boys. Of course, this was problematic for a young girl from a rural place in Nepal. Our schools were very far and we had to travel long distances to study. Families wouldn’t let girls travel far because they thought it was unsafe. So rather than dealing with us, they married us off early in life to get rid of what they considered as ‘a problem’.

As a child, I always wanted to study and become educated so that I would have the same opportunities as boys. Of course, this was problematic for a young girl from a rural place in Nepal. Our schools were very far and we had to travel long distances to study. Families wouldn’t let girls travel far because they thought it was unsafe. So rather than dealing with us, they married us off early in life to get rid of what they considered as ‘a problem’. My children have also gone through severe mental stress. In Kathmandu, I would work from 9am to 5pm every day. One day I came back to home to find my younger daughter and son crying. When I asked them why they told me that our neighbor had told them that I had gotten arrested. They remembered the time when I was gone for 15 days and began to panic. They didn’t know anyone else in Kathmandu and were scared about who would take care of them and feed them without me there.

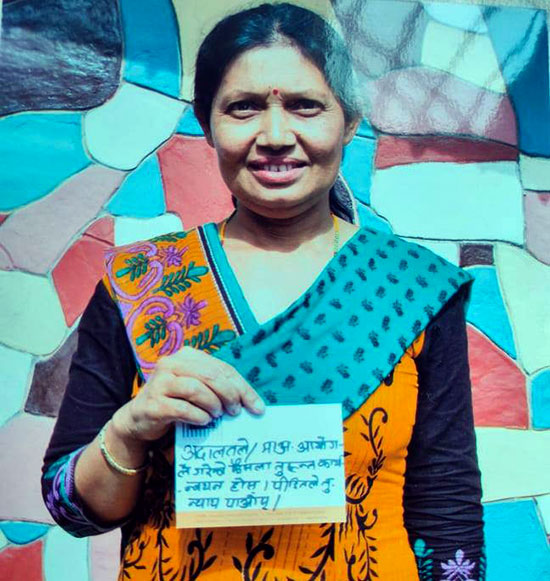

My children have also gone through severe mental stress. In Kathmandu, I would work from 9am to 5pm every day. One day I came back to home to find my younger daughter and son crying. When I asked them why they told me that our neighbor had told them that I had gotten arrested. They remembered the time when I was gone for 15 days and began to panic. They didn’t know anyone else in Kathmandu and were scared about who would take care of them and feed them without me there. On 1st June 2007, Supreme Court declared its verdict on my husband’s case. The court had decided that the army officials that abducted my husband should be arrested. But since Nepal had no law on disappearance, the court’s decision could not be implemented. After that the TRC and CEIDP were formed. But nothing has happened yet. During those days, someone told me about the International Courts where I could possibly get justice. Even though many people told me not to approach International Courts because it could create a difficult situation for me and my children, I still went ahead and did it. I filed a case and until this day, our case is ongoing at the International Labor Court.

On 1st June 2007, Supreme Court declared its verdict on my husband’s case. The court had decided that the army officials that abducted my husband should be arrested. But since Nepal had no law on disappearance, the court’s decision could not be implemented. After that the TRC and CEIDP were formed. But nothing has happened yet. During those days, someone told me about the International Courts where I could possibly get justice. Even though many people told me not to approach International Courts because it could create a difficult situation for me and my children, I still went ahead and did it. I filed a case and until this day, our case is ongoing at the International Labor Court.