When I was studying in grade 8, I joined the Maoist Movement.

I imagined a just nation where no one had to face any problems. This is why many of us were attracted to the movement. I was ready to die for the cause. ‘If my death makes my country better then it’s not a big deal for me to die’, these types of patriotic thoughts directed people towards the movement. The thought that poor people will get food to eat, no-one needs to face caste and class discrimination, and women will not be oppressed and get the same rights as men; all these ideas motivated me to join the movement.

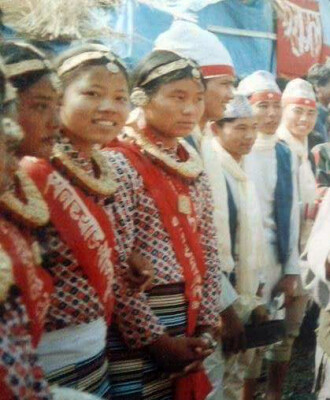

We had to be fit and well-trained. Biologically women are different than men but the training in our camps was the same both for male and female combatants. It was all about being courageous and breaking your mental barriers. We did everything that men would do. We would fight furiously at the forefront of the battles. Many of my friends became martyrs. I am one of the lucky ones who survived death.

I was born and raised as a child of a poor farmer in Faparbari, Makwanpur. Life in a village is difficult compared to the city. I could only go to school after finishing my household chores. I had no big dreams about what I wanted out of life. I don’t think I was ever taught to dream – rather to just accept my fate and live my life which would be filled with struggles. But I loved singing from a very young age. When I heard songs on the radio or television, I tried to copy and sing correctly. I would practice for ages.

During the movement, our life was tough. We would walk all night; sometimes from the hills to the terai. While walking we carried our musical instruments and food. We would stop in villages and stay with the villagers. We sang progressive songs, danced, and performed dramas. Our art was what inspired people to join the movement. Many people joined the movement, many supported. I think it was possible only because of this soulful artist’s front.

We would reach remote and far away villages. Our songs spoke of people’s sufferings. That’s how most people connected to us. Our songs work like medicine to their wounds of poverty and state of being. And many times it would work like an appeal to support the movement. We’d walk these downtrodden villages everywhere, throughout the country. We would walk from Tamang villages to the Chepang habitats. We would reach Thami villages and Dalit settlements. While traveling to all these areas, one thing I remember vividly is that – the nature of poverty and state oppression was exactly the same regardless of their geographical differences.

People in these villages and settlements welcomed us wholeheartedly. We went in there like a messenger and left as a family member. In some villages, our whole team would have to leave abruptly due to army patrol and raids. We’d run from those villages and sleep in the middle of the jungle. Wartime days were tough but they were worth it.

It was after the peace agreement that our leaders failed to protect us and the overall artists’ role became weaker. There was scarcity in the artist’s front but the leaders did not care. They would not directly tell us but their behavior showed that they didn’t need artists anymore. Many artists went back to their previous lifestyle of farming but many left for the Gulf countries in search of work.

Many of those who left to go abroad for work have returned home empty-handed. They still have that fury inside them against the system and the leaders. They say, ‘Even after all these years, things haven’t changed.’ I feel for them. I know the level of anger they must have inside them towards the leaders who failed to guide or protect them. The rising inequality and mass poverty that still exists in our country are unimaginable. Instead of working to increase our living standards, our leaders have turned to middlemen and mafias who constantly exploit their own population for labor, money, and resources.

We were very young then; maybe around 13 or 14 years old. But we weren’t naïve. We knew what we were getting into. All our socio-economic struggles in the village left no other options to fight for change. We wanted a drastic change in our system and that was the only reason why youth like me participated in the movement.

However, in our country, change has only been limited to words. Few words have changed here and there, but the situation of the country and its people hasn’t changed much.

After the peace process, I decided to continue my education. I completed my bachelor’s degree in journalism along with focusing on music lessons.

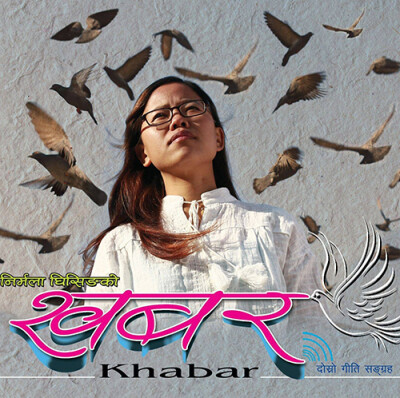

I started working at various radio stations. Though I was busy doing journalism, I wanted to engage myself more in music. So, I started networking with people in the music scene. Gradually I started to go to studios and getting offers for performing live. I got an opportunity to sing a song in a Tamang movie. In 2014, I released my first solo music album ‘Rahar’.

I was becoming more of a commercial singer. I had to, to sustain myself. At times, I wondered how my former comrades would see me in this commercial world. And at times, I wondered how my new audience would react if they find out about my communist background. Gradually both my comrades and audiences seem to pretty much accept the reality of who I am now.

After releasing albums and going around the world to perform, I’m still giving my best to create more opportunities and to preserve my existence in the musical world. I feel blessed to have supportive audiences and Chandra Kumar Dong and Maila Lama, my uncles, who inspired me a lot to continue.

Being a musician, I am trying my best to raise awareness in society through music. That’s what we did being a part of the musical front during the war. Now, all those memories of the war feel surreal.